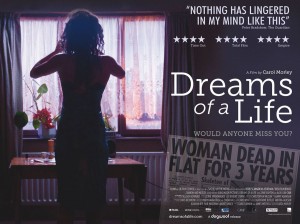

Carol Morley’s Dreams of a Life asks a question – “Would anyone miss you?” It is posed through the story of Joyce (Carol) Vincent, a 40-year-old, well-liked woman who died in her London flat in 2003, but whose body was not discovered for three entire years (by bill collectors, nonetheless). Almost completely disintegrated in the middle of her living room floor, Joyce Vincent’s only company was a television set that never turned off and half-wrapped Christmas presents for unknown recipients.

Framed primarily through interviews with people who knew Joyce Vincent in different capacities, and artistic re-imaginings of what Joyce Vincent may have been like (performed by British actress Zawe Ashton), Morley tries to piece together Joyce Vincent’s life and why, at the end of it, nobody knew that she was gone.

Dreams of a Life is a wonderful film for examining how staged dramatics can function within the realm of documentary film. Zawe Ashton transcends her role as an actress and becomes our conception of Joyce Vincent’s happiness, sadness, and the loneliness that underpinned her existence. The interview segments provide insight for framing Zawe’s actions, as people who knew Joyce Vincent in real-life remark at length about how beautiful, charming, and wonderful she was, but are completely at a loss for why nobody – themselves included – realized she was gone. The film is self-reflexive in this way, as Morley challenges the interviewees to understand why they failed Joyce Vincent. They are offered newspaper clippings and other material about Joyce Vincent’s life and death, and they react (usually with surprise) on camera. This eliminates the typical staginess of the documentary-interview, but is in direct contrast with how formally the interviewees are physically framed.

Dreams of a Life does not provide answers as much as it provides questions. It challenges the viewer to examine their own relationships with friends, family, and the world around them. It asks the viewer to explain why no one realized Joyce Vincent had disappeared. The haunting question that the film leaves viewers with is no longer “Would anyone miss you?” but “Why should anyone miss you?”