In her film Complaints of a Dutiful Daughter, Deborah Hoffmann details her mother’s memory loss before and after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The film is shocking in its unexpected portrayal of everyday tragedy. Hoffmann explains her experiences with her mother (Doris Hoffmann) directly into the camera, as if to indicate that she herself is emotionally ready to tell the story to a third party. The struggle and sadness she felt as her mother gradually began to forget aspects of daily life seems to be conquered through this film. Complaints of a Dutiful Daughter “was really done out of necessity,” Hoffmann states, because “it was an all-consuming situation that I needed to deal with in a film.”

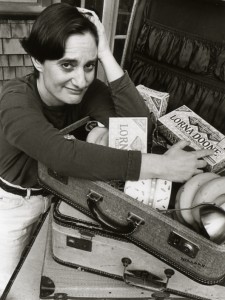

With a moving original soundtrack by Mary Watkins playing in the background, Hoffmann chronicles various stages of her mother’s descent into the illness. Hoffmann titles each stage: the Dentist Period is one in which Doris sees notes around her house saying that she has a dentist appointment, so she arrives at her dentist’s office every morning. Or the Suitcase Period, in which Doris would pack suitcase after suitcase full of anything she thought she could bring on a trip, which often left Hoffmann with full suitcases of Lorna Doone cookie boxes to unpack. Some of the stages seemed to indicate to Hoffman that her mother was trying to say something. The filmmaker interprets the suitcases as stating that Doris had lived alone in her home for long enough and that it was time for change. Eventually, as Doris could no longer even remember who her daughter was, Hoffmann moves her mother to a home in which she is separated from her past – separated from all of her possessions that could only cause frustration with the inability to remember any of their origins. Once settled in her new, more freeing environment (a location specializing exclusively in the care of Alzheimer’s patients), Doris “was used to it instantaneously.”

Hoffmann’s partner and the film’s cinematographer Frances Reid plays a fascinating role in the exploration of a person with Alzheimer’s disease. Hoffmann explains that throughout her life, her mother did not comfortably support her in her queerness. However as Doris ages, Hoffmann describes the way in which her life is more about the basics of love. A scene in the film reveals Doris declaring that Frances is “very nice to me and to [Deborah] – we all love her dearly.” Hoffmann’s work illuminates the beauty of the fact that discrimination and prejudice no longer exist in this elderly mind.

Complaints of a Dutiful Daughter received a nomination for an Academy Award® for Best Documentary Feature and in 1995 Hoffmann received the Peabody Award “for a remarkable and profound story of a mother and daughter’s courage in facing a debilitating disease.” The film aired on the 1995 season of POV, PBS’s showcase of acclaimed point-of-view documentary films, which created a partnership with the Alzheimer’s Association and the American Association of Retired Persons to “establish regional activities to raise awareness of resources available to Alzheimer’s care-givers and support groups.” The film also won both the Teddy and Caligari awards at the Berlin Film Festival. Before Complaints of a Dutiful Daughter, Hoffmann was already an accomplished film editor with credits including The Times of Harvey Milk and Color Adjustment.

“Hoffmann has made a loving, optimistic and authentic film about her mother, and the struggles to adjust to the changes wrought by Alzheimer’s disease.” ~William Fisher, Alzheimer’s Association, Greater San Francisco Bay Area Chapter