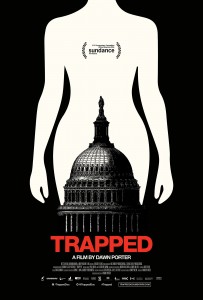

Trapped, written, directed, and produced by Dawn Porter, a 1988 Swarthmore graduate, follows abortion providers in the American South as their clinics are targeted by right-wing lawmakers. The documentary takes its name from the term “TRAP law,” which stands for targeted regulation of abortion providers. Examples of these regulations include requirements that doctors have permitting privileges at a local hospital, abortions be performed in surgical operating rooms, and certain medications must be available in clinics. In Trapped, Porter follows a doctor who describes how he has been turned away by the local hospitals explicitly because he performs abortions. A healthcare worker describes how patients receiving abortions often react with fear when led to the surgical operating room because the environment makes them believe that they will undergo surgery—which is not the case. A nurse describes how her clinic spends around $1,100 per month on required medications that no patient has ever needed; every month, the clinic throws away the expired, legally-required medicines.

Trapped succeeds in humanizing the doctors and nurses it focuses on. One doctor is asked if he is married; he responds that he would like to be, but he is married to his work. A nurse shares that her friends have begun encouraging her to retire, but she finds her work too important to walk away from. The intensity of the work abortion providers face is demonstrated but not fetishized in Trapped. One of the patients’ stories that is included near the end of the documentary is one of a 14-year-old girl who had been gangraped by four people. Another story is that of a 13-year-old girl who had been raped; this girl is turned away from the clinic in the documentary because the clinic was unable to find a legally required medical specialist who could meet with her. Neither of these patients are seen or heard from, but the effects of their stories on the doctors and nurses are seen. The nurse, describing how she had to turn away the 13-year-old, cries while she speaks. Trapped does not linger in this pain; after these scenes, there are calming shots of nature as the documentary transitions to a more upbeat ending sequence.

Near the end of the documentary, an anti-abortion group called Operation Save America demonstrate outside the clinic. They hold signs and shout at those entering the clinic. Others stand with signs in support of the clinic, and some wear yellow vests that designate pro-choice chaperones. A white anti-abortion protestor shouts at the black doctor that he is letting down his race by providing abortions to black women. In Trapped, examinations of race, class, and geography are included but not specifically highlighted. There is a comment near the beginning of the documentary about how the shutting down of clinics means that more people have to travel farther to receive safe abortions. Gender is also not a construct questioned by the documentary; there is no narration, and none of the text describes abortion in gendered terms. Different interviewees throughout Trapped describe abortion as a women’s issue.

Trapped tells the story of abortion’s legality. Archival material during the opening title sequence describes the impact of the 1973 Supreme Court Roe v. Wade decision; the first shot of original footage that comes after this sequence is dated to 2013, forty years after the landmark case. The effects of TRAP laws on abortion clinics and workers and their efforts to fight back are the focus of the documentary. The documentary ends with two victories—one clinic is able to remain open as the state Department of Health decides to not fight a lawsuit, and clinics across Texas are able to remain open as the Supreme Court places a stay on Texas House Bill 2. The relief felt is temporary, though; abortion is an area of healthcare that is shown to be under constant threat of being regulated out of existence. Trapped situates itself as a documentary about a slice of time in an ongoing battle.

Bibliography

This is a synopsis and review of Trapped published in the Catholic magazine Conscience. Trapped demonstrates the Christianity of its characters; Dr. Parker discusses his Christian upbringing and dedication to his work, and pro-choice activists pray together before Operation Save America protests against the clinic. (proquest, tripod)

This is a study on how political polarization affects the adoption of TRAP laws. Trapped includes footage of lawmakers but is more concerned with the effects of their legislation on abortion providers. (taylor&francis online, tripod)

Magda Werkmeister, 2019.