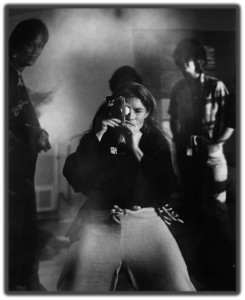

Indian women participate in a candle light vigil on the anniversary of the gang rape in 2012. (AP Photo/Tsering Topgyal)

Synopsis:

India’s Daughter tells the story of an infamous gang rape that occurred in New Delhi in 2012, and the protests and legal action that followed. It succeeds in portraying the heinousness of the crime committed and, through interviews with the victim’s parents and others, representing how horrifying and heartbreaking the event was. In terms of the other tasks that Udwin set out to accomplish — answering the question “why do men rape?” and unpacking the incident’s connection to its cultural context – the film not only comes up short, but constructs an actively problematic narrative. The film ties, sometimes implicitly but often explicitly, the rapists’ mentalities and motivations to their Indianness and to their poverty, a dangerously inaccurate representation. It also focuses heavily on the story of the rape and the lives of the convicted rapists, and very little on the organizing and activism undertaken by so many Indians in the months after the attack (only three people involved in protests are interviewed, each is on screen only once, for a minute or two).

After the first few minutes, in which the gang rape case is briefly described in voiceover, the film contains almost no overt narrative voice, in voiceover or on-screen text. The film is largely made up of interviews, the most prominent and controversial among them being an interview with Mukesh Singh, one of the men convicted of Jyoti Singh’s rape and murder (though he maintains that, while his brother and friends committed the assault and rape in the back of the bus, he was driving the entire time and did not commit the crimes himself). Much of the narrative work, then, is done through the juxtaposition of particular moments in different interviews. An exemplary instance of this narrative strategy is when Jyoti’s friend recalls Jyoti saying “A girl can do anything,” and the film cuts to Mukesh Singh saying “Boy and girl are not equal” (this quote is drawn from the English subtitles because Mukesh is speaking in Hindi – it is interesting to note that, though Hindi does not have articles, they chose not to supply them in the translation, making his speech appear improper or uneducated) and then shows shots of crowds of Indian men in public while Mukesh continues to recount his sexist views. While Jyoti and her family are heralded as progressive, the subtle work of the filmmaker presents Indian men, in general, as sexist and archaic. Besides interviews, the film contains a small amount of footage from the massive protests that occurred in the months following the rape, and some shots of the rapists being transported after their arrests and convictions. It also utilizes a vague form of reenactment — interviewee’s accounts of the rape itself are played over dark, blurry shots of a bus, the back of a driver’s head and hands, a religious figurine bouncing on the dashboard. These formal choices suggest a tendency of the filmmaker to amplify dramatic effect, perhaps at the expense of accuracy.

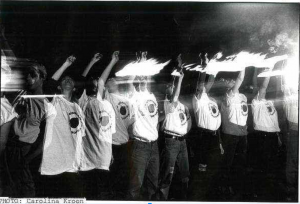

At the end of the documentary – over a still black and white shot of candles and a blood-spatter graphic – a list of statistics about gender-based violence in different countries scrolls across the screen. While this is presumably an effort to demonstrate how widely rampant violence against women is globally, it instead highlights the complete lack of international context given in the entirety of the film preceding. This last ditch attempt to broaden the film’s scope seems somewhat disingenuous in light of the overarching message that violence is the specific cultural product of a uniquely Indian misogyny. Though an account of the event itself would not necessarily need to incorporate an international context, the film’s fixation on Indian culture and its omission of any other contextualization creates the impression that rape is India’s problem. Particularly because this film was made for English-speaking audiences, i.e. primarily for outsiders to Indian culture, its myopic view leads to dangerous and counterproductive conclusions.

Suggested Uses:

I would only advocate the use of this documentary in very specific settings, among viewers already equipped with a background in intersectional and global feminism, wherein it might be consciously consumed and critiqued. It should not be turned to as an objective source of information on the facts of the case, as they are not carefully explained and one would do better reading about the incident.

Bibliographic Items:

Courting Injustice: The Nirbhaya Case and its Aftermath: A book by Rajesh Talwar on the legal changes made in India since 2012, the reasons the changes have not affected enforceability, and the cultural context in which all of this is taking place

Kavita Krishnan, prominent Indian feminist activist, on the Udwin’s white savior problem: http://www.dailyo.in/politics/kavita-krishnan-nirbhaya-december-16-indias-daughter-leslee-udwin-mukesh-singh-bbc/story/1/2347.html

Nilanjana S Roy, Indian journalist and writer, on the glaring absence of protestors’ and activists’ voices in the film: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/mar/03/indian-women-delhi-rape-film-rapist-indias-daughter