She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry (2014), Dir. Mary Dore

Synopsis: Dore’s film covers a huge range of issues in the rise of the women’s movement, mostly between 1966 (beginning a few years back with the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminist Mystique) and 1971. The documentary covers a range of issues the women’s liberation movement focused on, from abortion to birth control to equal pay to employment opportunities to self-defense and rape, and locates the beginning of the movement in the political energy of the Civil Rights, antiwar, and Black Power movements of the 1960s. The film also emphasizes the huge number of everyday, ordinary women who worked together to begin the movement, underscoring the role of consciousness-raising groups and collective organization rather than focusing on just a few women.

Formally, the film cuts often between interviews — always brief, interesting and relevant — and footage of past protests, speeches, and events, usually featuring the women interviewed. This effort to weave together interviews and past footage makes the film much more engaging than lengthy interviews or tape might be. SBWSA‘s interviews also lend a pleasing affective texture to the film, emphasizing the sense of women involved in the movement that it was long overdue as well as the catharsis and necessary support of consciousness-raising groups and a new (for white women, at least) understanding of the personal as political.

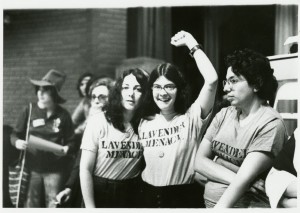

The film touches briefly on certain schisms within the women’s movement and towards the end focuses on the rollback of certain feminist gains such as abortion rights, but overall emphasizes the movement’s unity and triumphs — at the cost, perhaps, of truly delving into the painful and bitter exclusion of and alienation felt by Black women, for instance, from the feminist movement (the issue of lesbianism is given more time, but the Combahee River Collective’s statement and movement, though it emerges a few years past the film’s purview, would be an invaluable addition to the film — along with a few more minutes’ analysis of lesbian separatism, rather than what the documentary does, which is conclude that lesbianism was added and treated as important almost immediately by feminism after the Lavender Menace raised the issue). An unfortunate perpetuation of the universalism of the term “women” pervades the documentary, which, with a few notable exceptions in Fran Beal and Linda Burnham, focuses its interviews mostly on white women (a striking contrast with the footage and images from the past, which clearly show many Black women and other women of color involved in the organizing and activism taking place). The film could have made interesting connections between the ways in which certain spaces within the women’s movement would not permit the entrance of male infant children and modern day trans exclusion, or touched upon any number of issues which are brought up in the film but remain salient for the women’s movement (antifeminism from women, rape culture, etc.) but instead strikes a joyful and positive tone throughout. This is certainly in service of a noble goal of emphasizing the power of collective organizing, but misses the force which acknowledging difference and difficulty can generate.

Suggested uses: There is nothing new here — in fact, there is a lot missing — for those who have taken even an introductory Gender & Sexuality Studies class or studied the rise of feminism. Its most appropriate use might therefore be in high-school US history or possibly health classrooms, or as an engaging way in which to begin to study feminism’s development, though obviously much more research should still be done.

Bibliographic items: “The Woman-Identified Woman.” Written by the group of lesbian radical feminists calling themselves the Lavender Menace and responding to the exclusion of lesbians and lesbian issues from the feminist movement. The manifesto was passed out as part of a demonstration at the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City in 1970 (which did not feature any openly lesbian women). Often cited as a major moment and text in second-wave feminism, perhaps the foundational document for lesbian feminism. The next year, delegates at the 1971 National Organization of Women’s national conference declared lesbian rights a key concern for feminism.

The Combahee River Collective Statement and the anthology Words of Fire, ed. Beverly Guy-Sheftall, both of which provide more nuanced looks than the documentary at Black women’s role in women’s liberation.

The Kickstarter campaign for the film contains interesting information about the filmmaking process and creators’ purposes.