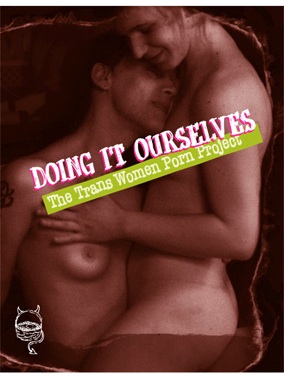

Doing It Ourselves: The Trans Woman Porn Project is a self-reflexive documentary that explicitly responds to the lack of non-fetishistic media and pornography by allowing trans women to represent their own sexualities with partners of their choosing.

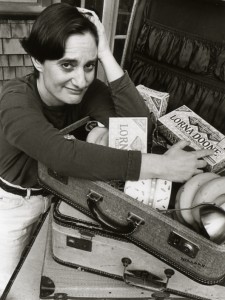

The first scene features Tobi Hill-Meyer, the filmmaker, coming home to the newest film by Trannywood, a studio that produces pornography exclusively featuring gay trans men. She sits down on her couch and begins watching the film and masturbating with a Hitachi. After she orgasms, two of her friends, also trans women, come in, and they discuss the lack of “trans dyke” porn. They decide that with Hill-Meyer’s filmmaking skills, they could make their own porn and she begins filming her friends kissing and then moving into a bedroom. There are three more scenes, each beginning with a brief discussion of performers’ experiences with pornography and what they are expecting from their scene. The film features trans women in scenes with each other, with trans men, and with cis women, often in pre-existing relationships. The performers vary widely in gender presentation and consent is clearly verbally negotiated during sexual encounters, with participants laughing and admitting when things are uncomfortable.

Rather than fetishizing the bodies and especially genitalia of trans women as anomalous, the film emphasizes whole people and interpersonal dynamics. This is done with self-reflexive cinematography. The performers actively discuss filming themselves and there are frequent shots of the performers in the LCD display of the camera. In contrast to mainstream pornography, which shows genitals in intrusive, sensationalized close-ups, Doing It Ourselves features more medium shots, which focus on skin and body movement, frustrating habitual audience attempts to scrutinize physical differences. The performers’ identities also normalize gender and sex variation; surgical status is not emphasized in any way. The DVD extras feature interviews with all the performers, humanizing them and allowing them to speak for themselves about other parts of their lives aside from sex. Hill-Meyer also uses her work to build community, interacting online via tumblr and giving interviews in small queer publications.

Hill-Meyer is planning a sequel, Doing it Again: In Depth, which will be about how trans women navigate relationships and hooking up, both with trans and cis partners. It will explore how intersections such as race, class, ability and survivor status influence how trans women connect and flirt with sexual and romantic partners. It will be released as a two volume DVD, with a volume each on trans women with trans partners and trans women with cis partners. The Kickstarter campaign for the film raised enough funds that a third volume will be made about genderqueer and gender non-conforming trans women, as well as trans women with genderqueer and gender non-conforming partners. The open casting call again encourages people in mid and long term relationships to apply to represent intimate interpersonal dynamics, as well as identities that are underrepresented in pornography, such as people of color, people over forty, and trans men.