Source: delmarvalife.com

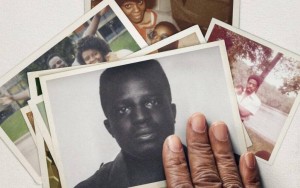

Filmmaker: Yance Ford

Year: 2017

Running Time: 107 minutes

Country of Origin: United States

Streaming: Netflix

Synopsis:

Filmmaker Yance Ford, in this achingly personal documentary, investigates the 1992 murder of his older brother, William Ford Jr., chronicling the arc of a family across history, geography and tragedy. Ford traces his familial history from the racial segregation of the Jim Crow South to the promise of New York City, through multiple generations affected by the socio-political tides of New York. Prominently featuring the Ford family — Barbara Dunmore, William Ford and their three children — the film explores how the lives and communities which surround Yance Ford were shaped by the enduring tensions of race in America. A deeply intimate and meditative film, featuring frequent appearances by the filmmaker disrupting the fourth wall and addressing the viewer in the self-reflexive documentary style, Strong Island poses questions around racial injustice in contemporary America and how complicity, grief, and silence continue to affect the pursuit of justice.

While the film looks at the injustice surrounding the murder of William Ford Jr., the interview style of Ford’s family and Ford himself examines themes of resilience, overcoming grief, guilt, and the intersection at which Yance Ford’s identity as a queer, trans black artist is silenced in the course of tragedy. While the ‘queering’ of the documentary style is subtle in Strong Island, Ford’s high-contrast, head-on self-interviews is jarring and new to the otherwise traditional documentary style of the film, replete with medium shot interviews, recreations, archival images and documents. Instead of being kept at a safe distance, audience members are forced to very literally sit near and within the emotionally-tortured head of the filmmaker himself. The courageous self-exposure in these moments of grief, pain, and tension disrupts the otherwise pre-packaged formulae of commercial true crime docs.

Articles/Readings:

“Towards Trans Cinema,” Eliza Steinbock

(Chili Shi ‘22)