Image Source: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0098414/

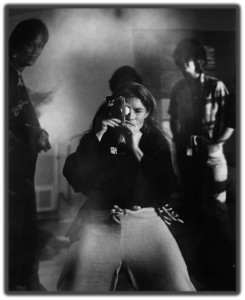

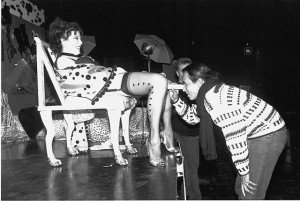

In Surname Viet, Given Name Nam (1989), Trinh T. Minh-Ha deconstructs the idea that documentary reveals the “real world,” especially within the context of the ethnographic interview, and critiques the ways “ideologies of authenticity legitimize exclusionary systems of representation” (Gracki, 53). In the first half of the film, the audience is shown a series of first-person interviews, seemingly of Vietnamese women in Vietnam, intercut with newsreel footage, still photos of the Vietnam war, and footage of traditional folk dances. The interviewed women are dressed in the simple attire of socialist Vietnam, a “feminist natural look,” forming an impression of a “natural” portrayal of the Vietnamese feminist activist, and the footage aligns with and reproduces popular Eurocentric conceptions of Vietnam. In the second half of the film, this illusion of an “authentic” representation is shattered as the previously seen women are revealed to be non-professional Vietnamese actresses living in California – the interviews are, in reality, reenactments of the translated and transcribed interviews originally conducted by Mai Thu Van in Vietnam: un peuple, desvoix. In the second half of the film, Minh-Ha interviews the actresses, questioning them on why they agreed to be a part of the film, and displays footage of them in their day-to-day, “real life” activities. In these interviews, the women no longer dress in costume, and are able to choose their clothing — this time, it appears to be a more “genuine” account of them. Yet, even now, in these “real” interviews, the women choose to wear showy clothing and makeup that they don’t wear in ordinary life, and choose backgrounds for the interviews, such as a fish pond, that don’t represent their own lived realities. Paradoxically, the performative nature of this self-representation is able to reveal more about their lived experience as working class women, and in this way, Minh-Ha illustrates how “fictionalization need not be associated with fraud, duplicity and lies, for it is ultimately able to draw out a greater truth than the mere attempt to mirror ‘reality’ and everyday life” (Gracki, 52). Ultimately, Min-Ha exposes the way ethnographic films and film makers construct authenticity for ideological reasons, and the way these neocolonial narratives of authenticity “exclude, silence, and objectify Third World Women within debilitating stereotypes that not only deny them agency and subjectivity, but make this lack appear somehow ‘natural’ and inevitable” (Gracki, 53).

Bibliographic item:

To understand the intentions behind and develop a greater understanding of the critical theory surrounding Surname Viet, Given Name Nam, it may be helpful to read the book Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism, especially Chapter 3: Difference: “A Special Third World Woman Issue,” and the journal article Documentary Is/Not a Name, both written by Trinh Minh-Ha. I also found the journal article True Lies: Staging the Ethnographic Interview in Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Surname Viet, Given Name Nam (1989) by Katherine Gracki to be incredibly enlightening in attempting to understand the film and getting a background to its creation, release, and reception.

Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism: https://tripod.swarthmore.edu/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991018893369004921&context=L&vid=01TRI_INST:SC&lang=en&search_scope=SC_All&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=Everything&query=any,contains,woman%20native%20other&offset=0

Documentary Is/Not a Name: https://www.jstor.org/stable/778886?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

True Lies: Staging the Ethnographic Interview in Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Surname Viet, Given Name Nam (1989): https://www.jstor.org/stable/3595469?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents